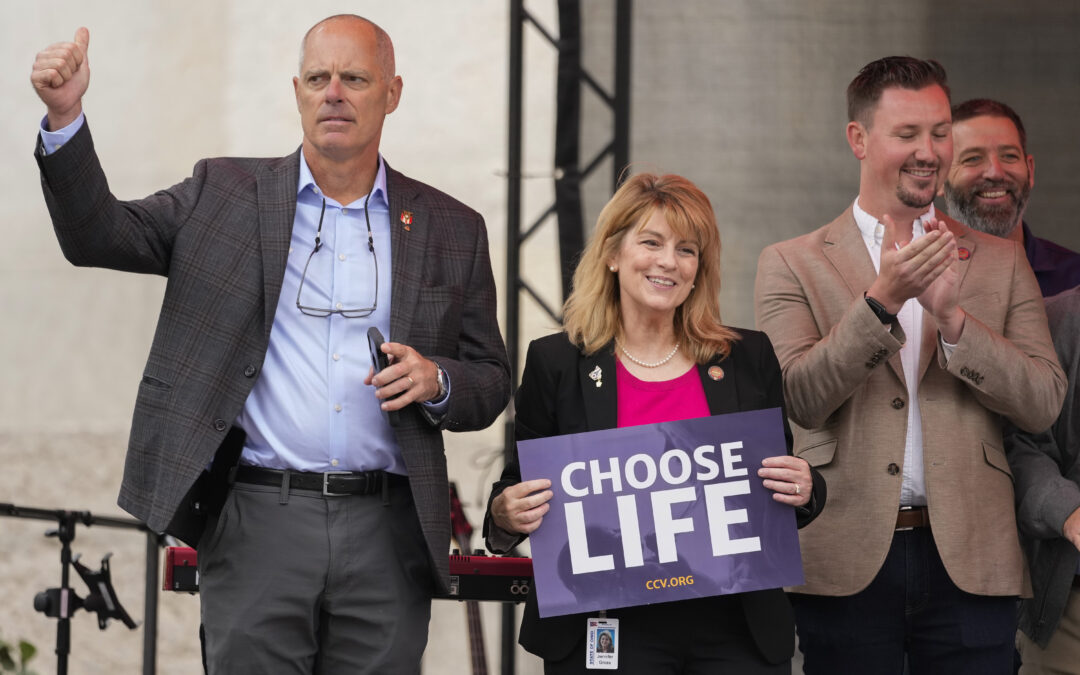

By JULIE CARR SMYTH and CHRISTINE FERNANDO Associated Press | Ohio State Rep. Jennifer Gross, R-West Chester, holding a “Choose Life” sign, center, joined by Ohio State Rep. Adam Bird, R-New Richmond, left, and Ohio State Rep. Thomas Hall, R-Madison Township, right, stand together on stage during the Ohio March for Life rally at the Ohio State House in Columbus, Ohio, Oct. 6, 2023. The statewide battles over abortion rights that have erupted since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a constitutional right to the procedure have exposed another fault line: commitment to democracy. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

COLUMBUS, Ohio (AP) — The statewide battles over abortion rights since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a constitutional right to abortion have exposed another fault line: the commitment to democracy.

As voters in state after state affirm their support for abortion rights, opponents are acting with escalating defiance toward the democratic processes and institutions they perceive as aligned against their cause.

Certain Republican elected officials and anti-abortion activists around the country have responded to losses at the ballot box by challenging election results, refusing to bring state laws into line with voter-backed changes, moving to strip state courts of their power to consider abortion-related laws and challenging the citizen-led ballot initiative process itself.

“We.Are.Not.Done.,” Ohio state Rep. Jennifer Gross declared on the social media platform X two days after voters enshrined the right to abortion in the state constitution earlier this month. She and 25 other Republican lawmakers vowed to block the amendment from reversing Ohio’s existing abortion restrictions.

A strong majority of Ohio voters passed the amendment, by roughly 57% to 43%. In response, the group of lawmakers said in a joint statement: “We will do everything in our power to prevent our laws from being removed based upon perception of intent.”

Gross joined three fellow Republicans to go even further, proposing legislation to prevent Ohio courts from interpreting any cases related to the abortion-rights amendment, known as Issue 1. Similar efforts have emerged in six other states since state courts became the new abortion battleground after the Dobbs decision on June 24, 2022, that overturned Roe v. Wade.

Douglas Keith, senior counsel to the Brennan Center for Justice’s Judiciary Program, said abortion politics prompted successful efforts to limit the power of state courts in Montana and Utah and unsuccessful legislation in Alaska and Kansas. Such bills are attempts to dismantle the government’s system of checks and balances, he said.

“An attempt to strip the courts’ ability to interpret Issue 1 seems to me to be picking a fight with not just the courts, but with voters themselves,” Keith said in reference to the Ohio amendment.

That conflict was on display during a town hall hosted by Gross after her efforts to thwart the abortion-rights amendment were announced. A constituent who said she supported Issue 1, Emily Jackson, was incredulous.

“You’re ignoring the voice. The voice is there,” Jackson said. “We spoke.”

Gross told Jackson she wasn’t ignoring voters but rather was reflecting opponents’ concerns that Ohio voters were led astray. The campaign drew big money from outside the state for both sides.

Gross did not return call and emails seeking additional comment.

Advocates contend that strict abortion laws also are undemocratic in the most basic sense because a majority of Americans oppose them. According to AP VoteCast, a nationwide survey of more than 94,000 voters, 63% of those who voted in the 2022 midterm elections said abortion should be legal in most or all cases. An Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll taken a year after the Supreme Court’s decision found that about two-thirds of Americans overall said abortion should generally be legal.

In all seven states where abortion has been on the ballot since Roe v. Wade fell, voters have either supported protecting abortion rights or rejected an attempt to erode them.

That has led some Republicans who support abortion restrictions to target the ballot initiative process, a form of direct democracy that is available to voters in only about half the states.

“Thank goodness that most of the states in this country don’t allow you to put everything on the ballot because pure democracies are not the way to run a country,” said Rick Santorum, a former U.S. senator from Pennsylvania and one-time presidential candidate. He spoke about Ohio’s election results during an appearance on the conservative site NewsMax.

Another elected Republican, North Dakota state Rep. Brandon Prichard, weighed in on X, formerly Twitter, to encourage Republicans to defy the outcome of Ohio’s election.

“It would be an act of courage to ignore the results of the election and not allow for the murder of Ohio babies,” he wrote.

Some political observers see a larger danger in such sentiments.

Sophia Jordán Wallace, a political science professor at the University of Washington, said “the frequency and the explicitness of these undemocratic attempts are increasing” and that they threaten to do long-term damage to American institutions and the public’s faith in them.

“And that damage is incredibly difficult to undo,” she said.

For many abortion opponents, the issue is “a sacred cause, the thing that cannot be argued with,” one that may outweigh the importance of maintaining democratic practices, said Myrna Perez, associate professor of Gender and American Religion at Ohio University.

“Things aren’t static, so you’re trying to figure out a way to get the system to give you the results that you want,” she said.

Andrew Whitehead, associate professor of sociology at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, said Christian nationalists, who have deep ties to the anti-abortion movement, have a history of viewing access to fundamental democratic processes such as voting not as a right but a privilege that should be afforded only to those who align with their beliefs.

“When it comes to enforcing their vision for America they think is ordained by God, they will set aside democracy,” Whitehead said.

Anti-abortion lawmakers and advocates already have pushed back in a handful of states where voters sided generally with abortion rights.

In Montana, voters last fall rejected a legislative referendum that would have criminalized a doctor’s or nurse’s failure to provide lifesaving care to a baby born alive after an attempted abortion; such cases typically involve severe medical problems. Republicans countered by passing a version of the rejected measure into law.

Kentucky Republicans chose to leave intact a state ban on abortion at all stages of pregnancy, even though voters there defeated a measure that would have denied constitutional protections for the procedure.

In Ohio, some notable top Republicans are rejecting anti-democratic suggestions and standing up for voters.

“In this country, we accept the results of elections,” said GOP Gov. Mike DeWine, a leading opponent of Issue 1. Republican Attorney General Dave Yost tweeted that he “scoured” the Ohio Constitution, but found “no exception for matters in which the outcome of an election is contrary to the preferences of those in power.”

“All political power is inherent in the people,” he quoted the document as saying.

Republican state legislative leaders initially pledged that the fight to restrict abortion rights wasn’t over after voters had spoken. But as their party grapples with the anti-abortion movement’s deep divisions, House Speaker Jason Stephens and Senate President Matt Huffman have appeared to soften their tone.

Stephens signaled he won’t advance Gross’s court-limiting bill. Huffman, a devout Catholic, walked back suggestions that he could pursue an immediate repeal of Issue 1.

They were among Ohio Republicans who defied their own law and called a special election in August aimed at raising the threshold for passing future constitutional amendments from a simple majority to 60%. The measure was widely seen as an attempt to undermine the fall abortion amendment and was soundly rejected.

The tensions already are evident for abortion initiatives planned for state ballots in 2024.

In Missouri, disputes over ballot language are complicating efforts by abortion-rights supporters to advance a statewide ballot measure. A panel of judges last month ruled that summaries written by Republican Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft, an abortion opponent who is running for governor next year, were politically partisan and misleading.

In Michigan, three Republican lawmakers joined an anti-abortion group in suing to overturn a state constitutional amendment protecting abortion rights that voters passed with wide support last year. Florida’s Republican attorney general is attempting to keep a proposed abortion rights amendment off the 2024 ballot.

“We saw voters make that connection in Ohio between abortion and democracy in that first special election,” said Kara Gross, legislative director at the ACLU of Florida. “And we have faith voters will be able to make that same connection elsewhere in 2024.”

The Associated Press receives support from several private foundations to enhance its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. See more about AP’s democracy initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.