By HEATHER HOLLINGSWORTH Associated Press

A FRIENDSHIP BRACELET WITH A PHONE NUMBER

That’s how Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce planned to woo superstar Taylor Swift when he went to her Eras Tour concert stop in the Missouri capital. It didn’t work — at first.

But the romantic gesture, and public admission of defeat on his “New Heights” podcast, caught the Grammy Award-winner’s attention. After the power pair took their relationship public — she went to a Chiefs game and sat in a box with Kelce’s mom, to the delight of fans — they began taking the world by storm.

Sportscasters calculated Swift’s effect on Kelce’s game stats and TV viewership, national magazines offered up comprehensive dating timelines, and Swift fans scoured Kelce’s old social media posts to make sure he was fit for their queen.

On tour in Buenos Aires, the then-33-year-old singer changed a lyric from “Karma is the guy on the screen” to “Karma is the guy on the Chiefs.” And fans went crazy when she jumped into Kelce’s arms for an iconic post-concert kiss.

“I think we’re all excited about it. Until they start making good romcoms again, this is what we have,” said Michal Owens, a 37-year-old longtime fan from the Indianapolis suburb of Zionsville.

While pint-sized pairs of trick-or-treaters donned glitzy dresses and Chiefs jerseys this Halloween, Owens transformed her outdoor display into a tribute. The mother of three dressed one 12-foot-tall (3.66-meters-tall) skeleton in a Chiefs jersey, another in a sparkly dress and then stacked three smaller skeletons atop one another to create what she called a “tower of Swifties.”

“We’ve got so many things in the world to be sad about,” she said. “Why not find something to root for and give us some joy?”

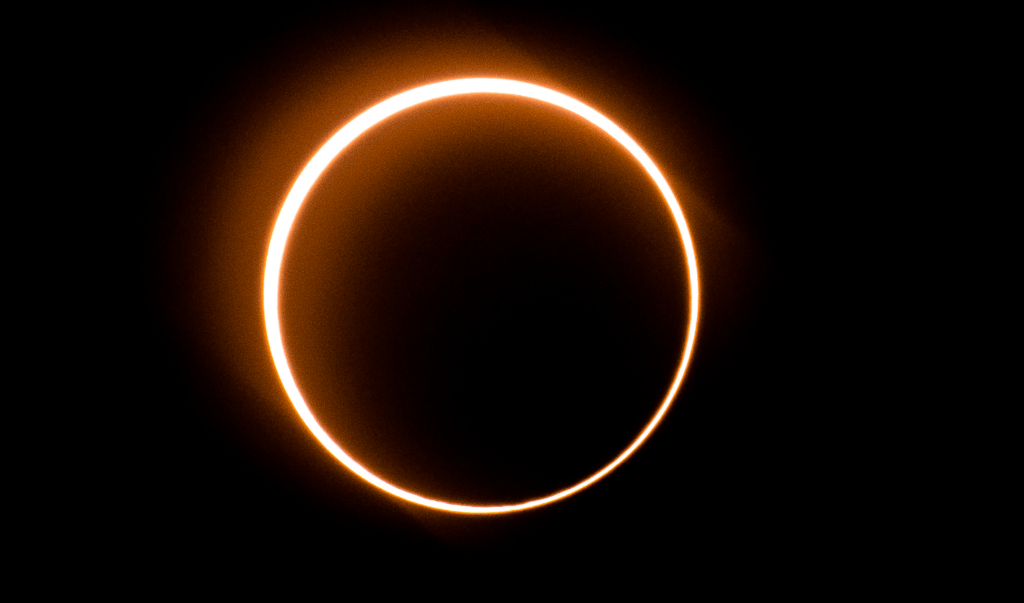

AN AWE-INSPIRING ECLIPSE

From Oregon’s coast to the beaches of Corpus Christi, Texas, millions of people in October donned special glasses and gazed upward to take in the dazzling “ring of fire” eclipse of the sun.

“It’s kind of spiritual, but in a way that is almost tangible,” University of Texas at San Antonio astrophysics professor Angela Speck said as she recalled the type of eclipse that ancient Mayan astronomers called a “broken sun.”

Crowds in the path of the eclipse erupted in cheers when the moon blocked out all but a brilliant circle of the sun’s outer edge. Participants at an international balloon fiesta in Albuquerque, New Mexico, whooped from the launch pad. Broadcasters for NASA said they felt a chill as the moon cast a shadow over the earth — and one broadcaster was so overcome with emotion that she began crying.

The phenomenon was a prelude to the total solar eclipse that will sweep across Mexico, the eastern half of the U.S. and Canada, in April 2024. But the next “ring of fire” eclipse won’t be visible in the U.S. until 2039 and then only in parts of Alaska.

IN DEATH, A SELFLESS ACT

Surprise letters are showing up in mailboxes, informing recipients that their medical debt is wiped away.

They have Casey McIntyre to thank. The 38-year-old New York City book publisher nearly died of cancer in May. But in what her husband, Andrew Rose Gregory, called a “bonus summer,” the young mother made plans to help people after she was gone. Her goal: To erase medical debt.

In a message posted after her death in November, she asked for donations, writing, “I loved each and every one of you with my whole heart and I promise you, I knew how deeply I was loved.”

By December, the campaign had raised more than $1 million, enough to erase around $100 million in debt. That’s because the nonprofit RIP Medical Debt says every dollar donated buys about $100 in debt.

“Her positive spirit is just resonating with a lot of people,” said Allison Sesso, the nonprofit’s president and CEO.

The effort was inspired by the people McIntyre met during treatment. They weren’t just worried about their health but how to pay for their care. She had good insurance — and “couldn’t even fathom having to deal with that on top of the cancer,” Sesso said.

The fundraiser, which quickly shattered its initial goal of $20,000, gave her family a sliver of “something positive” to focus on amid their grief. It was particularly hard for the family because when McIntyre died, her daughter was just a toddler, not yet 2.

“This sounds crazy but she didn’t seem angry at all,” said Sesso. “She was like, ‘This happened. I’ve accepted that this has happened, and I’m going to do this positive thing.’”

A SPIRITUAL HOMECOMING

When the Grand Canyon became a national park over a century ago, many Native Americans who called it home were displaced.

In 2023, meaningful steps were taken to address the federal government’s actions. In May, a ceremony marked the renaming of a popular campground in the inner canyon from Indian Garden to Havasupai Gardens, or “Ha’a Gyoh,” in the Havasupai language.

It marked a pivotal moment in the tribe’s relationship with the U.S. government nearly a century after the last tribal member was forcibly removed from the park. The Havasupai Tribe was landless for a time until the federal government set aside a plot in the depths of the Grand Canyon for members.

Then in August, President Joe Biden signed a national monument designation — over the opposition of Republican lawmakers and the uranium mining industry — to help preserve about 1,562 square miles (4,046 square kilometers) to the north and south of Grand Canyon National Park.

It was another big step for the Havasupai, and for the 10 other tribes that consider the Grand Canyon their ancestral homeland.

The new national monument is called Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni. “Baaj Nwaavjo” meaning “where tribes roam,” for the Havasupai people, while “I’tah Kukveni” translates to “our footprints,” for the Hopi Tribe.

The move restricts new mining claims and brings tribal voices to the table to manage the environment, said Jack Pongyesva, of the Grand Canyon Trust, an advocacy group that represents tribal and environmental issues in the region.

He said it also could open the door for more cultural tourism, where visitors could learn not just about the landscape but about the tribes — from the tribes themselves.

Pongyesva, a member of the Hopi Tribe, said the dedication is “The beginning of hopefully this healing and looking back and seeing what was wrong and moving forward together.”

A RESILIENT RETURN

Firs are mainstays of Christmas tree lots. But on the Isle Royale National Park near Michigan’s border with Canada, balsam firs were being devoured.

Gray wolves on the remote island cluster in Lake Superior were already dying out from inbreeding, causing the moose population to become a “runaway freight train” and strip the trees during long, snowbound winters, said Michigan Tech biologist Rolf Peterson.

An ambitious plan was hatched to airlift wolves from the mainland to the park — and it’s starting to make a big difference. A report this year shows the resurging wolf population is thriving and the moose total is shrinking, giving the trees a chance to recover.

There were critics of the plan, but Peterson said there weren’t other viable options. Because of climate change, particularly global warming, there are fewer ice bridges, reducing wolves’ ability to trek from the mainland and diversify the gene pool.

“That was a huge undertaking,” Peterson said, and it turned out “spectacularly well.”